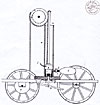

To the right is de Rivaz' 1807 'car'. It was propelled by his combustion engine, patented two years earlier.

The pre-history of the "spark-ignited engine" starts with Huygens who first has the idea, in 1673, to use the dilation of gases to force movement such as in a motor. His machine consists of the two basic components, a cylinder with a piston inside. A gunpowder sash is placed at the bottom of this pump where, after ignition, the resulting explosion displaces the air inside the cylinder, forcing it out through a valve. The resulting vacuum, due to the pressure difference between it and the atmospheric pressure, forces the piston backward. The transfer of power is proposed by the means of a pulley system. Abbot Jean Hautefeuille (1647-1724) and Denis Papin (1647-1714), Huygen's assistant, also conduct experiments to harness the power of explosions. Others follow the example and experiment with the basic concept of creating a vacuum via an explosion. Many of these experiments are interesting but they are somewhat difficult to recognize as the conceptual precursors of genuine combustion engines.

The "spark-ignited engine" makes its debut in history roughly in the 1790s. The first names recognized are those of the two Englishmen who first filed patents on such engines; John Barber on October 31, 1791 and Robert Street on May 7, 1794, although these inventors did not continue to refine their machines. It is also the case with Frenchman Philippe Lebon (1769-1804) who obtained his patent on August 25, 1801.

The first construction recognized as an - genuine - engine is due to the French Claude and Nicephore Niepce whom received their patent on April 3, 1807. This engine, the "Pyreolophore", used the dilation of the air following a sudden ignition of a fuel mixture in a cylinder with a piston. Simultaneously, as the Niepce brothers were filing their patent, they were informed of

"the inventions of de Rivaz". It is difficult to deduce how they

may have used this information in their subsequent patent filing. Aside from the

essential principle,

"the inventions of de Rivaz". It is difficult to deduce how they

may have used this information in their subsequent patent filing. Aside from the

essential principle,  which

is to produce a combustion in the interior of a cylinder, the "Pyreolophore"

differs significantly from de Rivaz' engine.

which

is to produce a combustion in the interior of a cylinder, the "Pyreolophore"

differs significantly from de Rivaz' engine.From 1807 on the projects and the patents for new types of engines multiply. The years until 1860 see more than thirty patents filed, applicable to internal combustion engines and their components. Some of the better known are those of the English Samuel Brown (1823 and 1826) and William Barnett (1838), the Italian Eugene Barsanti (1854) and the French Degrand (1858) and Hugon (1858).

The year 1860 marks a turning point when Etienne Lenoir (1822-1900) builds his remarkable gas engine. His engine introduces one of those key innovations which defines subsequent designs, for a long time. (Lenoir's 1-Cylinder engine was a horizontal arrangement and his 'car' was termed the "Hippomobil" because it generated it's fuel - hydrogen - via the electrolysis of water. This engine was later adopted to use various other gases, such as the one derived from coal etc. This coal-gas burning engine variety is the one which ultimately found commercial acceptance - auth.)

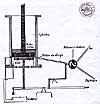

Lenoir's "Hippomobile". It was a 1-Cylinder, horizontal arrangement, powered by

hydrogen, generated via the electrolysis of water.

Lenoir's "Hippomobile". It was a 1-Cylinder, horizontal arrangement, powered by

hydrogen, generated via the electrolysis of water.Like a couple of inventors before him, Lenoir seems to be inspired by the fact that the machine had "natural cycles", during one of which, two of the basic engine functions can be combined -- A) Uptake of the fresh fuel-mixture; and B) Exhaust of the combustion vapors. Beau Rochas finds the same cycle in 1862, which bears his name today. The later came upon his discovery while trying to improve the energy conversion of the engines and substitutes a liquid fuel mixture instead of coal gas. Shortly after he conceptualized the four-stroke engine. It is notable that

de

Rivaz had also introduced a "clean cycle" into his engine's operation, half

a century earlier. In 1862 the vehicle powered by Lenoir's engine completes the

18 kilometers between Paris and Joinville just under 3 hours.

de

Rivaz had also introduced a "clean cycle" into his engine's operation, half

a century earlier. In 1862 the vehicle powered by Lenoir's engine completes the

18 kilometers between Paris and Joinville just under 3 hours.Around the same time (1861) the German Otto builds an engine bearing quite a resemblance to that of de Rivaz' machine. Otto places the cylinder vertically, with the opening on top. Between the piston and the bottom of the cylinder there remained a space where a mixture of air and coal gas was injected. Following ignition, the resulting explosion drives the piston upward until it reaches the summit of the cylinder. Consequently a vacuum is produced under the piston and thus, the piston travels down again, pushed by its own weight and by the atmospheric pressure. The cycle repeats and this movement actuates a wheel shaft from which a series of cogs ultimately drive a wheel. This version of Otto's motor is almost identical to the "engine of de Rivaz". It is only in 1876 when Otto realized another engine, functioning according to the Beau Rochas cycle. Consequently, "engine spark-ignition" technology had reached a point of maturity where it could be practically applied to the propulsion of cars.

In the subsequent years it will be for the efforts of the French Delamare-Debouteville (1883 and 1884) (Patent No: 160 287,160 288; Paris; Expired in 1901), whose 2-Cylinder engine design was the first purely petroleum motor and which later gave rise to the De Dion et Bouton motors, and especially those of the German Daimler, Benz and Maybach (1883 through 1888) which bring into service genuine motor vehicles with "spark-ignited engines".